A Short History of Paper Boats.... and more.

Step back briefly to Troy NY in the mid-19th century in Upstate NY. (The above illustration is from about 1840). Few towns across the United States matched Troy, New York, in prosperity. Several miles north of Albany, the town faces the eastern terminus of the then active Erie Canal on the farther bank of the Hudson. Earlier in the 19th century, Adirondack charcoal and iron ore came in by water and fueled a lucrative local steel industry. As the steel industry moved west, precision manufacturing industry sprang up. Troy also acquired a special fame as the originator and nationwide supplier of detachable paper collars and cuffs. Eventually millions were manufactured and sold every year.

Into this environment arrived a teen-aged Elisha Waters who moved with his parents and family fom Bennington, Vermont to Troy in 1831. He apprenticed with several retail druggists and eventually opened a drug business of his own offering a variety of items of his own manufacture such as inks, tonics, and remedies, including "Waters' Pulmonica". But he apparently saw another business opportunity in box manufacturing. By 1862 he had abandoned the drug business and his primary enterprise was a prosperous factory that made boxes for local industries and retailers.

One early March day in 1867, the box baron"s teenage son, George, received an invitation to a masquerade party and decided to attend as a giant. He designed a costume and found a giant-sized face mask in a local store. But the eight-dollar price exceeded his budget. Undaunted, he arranged to borrow the mask and layered paper and paste over it at his father's factory to create a copy.

This new kind of paper work prompted George to reexamine a used rowing shell he often took out on the Hudson (a cast-off from Josh Ward, a famous rower of the period). The boat leaked badly and required patching, and he lit upon the idea of gluing pieces of thick paper to the hull and then coating them with varnish. With this success in hand, he wondered if an entire boat made of paper and varnish might work.

In June, George and his father set to work, using the hull of another wooden rowing shell as a mold, to create an altogether new type of craft whose skin was formed from a single sheets of paper extending unbroken from stem to stern, leaving no joints, laps, or seams on the surface. The hull proved to be light and strong. The father-son team had created the first practical paper boat that could successfully carry a human being and christened it the "Experiment".

During the remainder of 1867, George and Elisha built three more hulls and refined the process. The family team patented the process and shortly thereafter formed the firm of Waters and Balch, (later to become Waters & Sons). Their invention marked a turning point for the family business. The 1868 Troy city directory no longer listed Waters as a box manufacturer but as a boat maker. In 1932 George Waters' other son, Charles Vinton Waters, told the trade journal Superior Facts that "after the victory of Cornell, rowing a paper six-oared shell, over twelve other colleges in wooden boats at Saratoga Lake in 1875, followed by a clean sweep of all events at the Centennial Regatta in 1876, they were in general use in this country for more than thirty years."

At the peak of their popularity, the paper armada eventually ranged from simple single-person rowing shells to a 45-foot "pleasure barge," which could comfortably seat 17, not counting six toiling oarsmen. In 1875 the New York Daily Graphic could confidently assert that this family, which eight years earlier had only built the likes of hatboxes, now operated the "largest boat factory in the United States."

The use of paper meshed with shifts in technology at the time. More than a few historians have dubbed the latter half of the 19th century as the "Age of Paper." The Fourdrinier brothers new and phenomenally productive "Fourdrinier Machine", (invented by a Frenchman, Nicholas Robert), was for the first time providing large quantities of paper in long, continuous rolls. Before this machine, paper was made by hand on a large frame, containing a screen, dipped into a large vat of water and paper pulp. The size of the sheet was limited by the size of a frame that could easily be handled by one or two papermakers. The Fourdrinier machine overcame this bottleneck by using a rotating screen belt to receive the pulp.

(A nice YouTube video of hand paper-making can be found at here ; for a tour of a modern paper making factory try this link.

Another shift in technology was the increased use of wood pulp for paper. Formerly virtually all paper was made from linen or cotton rags. With the increased industrialization and the increased demand for paper, the demand simply outstripped the supply. However by 1854 chemists had developed processes to free the cellulose from the wood fibers providing a plentiful and inexpensive alternative to rag for many applications. The price of paper pulp and paper fell drastically.

In an age without plastic or composite materials, this new inexpensive paper, which could be molded, formed, and otherwise manipulated, became the high-tech construction substance of its day. Inventions ranged from clothing - (an entertainer, Mr. Howard Paul sang "The Age of Paper" in British music halls, clad head to toe in his subject material) - to boats, observatory domes, flowerpots, and even coffins.

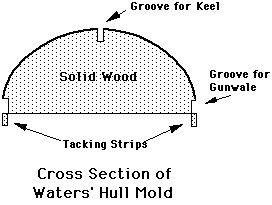

The fabrication technique followed by Waters & Sons throughout these years differed little from that presented in the original patent. A full-size convex wooden model was prepared to the exact desired dimensions. The mold was solid, but it had grooves cut into it so that a keel could be inserted along the keel line and similar strips along the gunwales. Below the gunwales, "tacking strips" were attached that enabled the paper to be stretched over and tightly fastened to the mold.

For lightweight boats such as racing shells, Waters & Sons used the best grade of manila paper, which in the 19th century was made directly from manila hemp. Several layers were applied, each sheet running the full length and breadth of the molding hull. The first sheet was applied slightly damp, then tacked down and coated with an adhesive to accept the next sheet. After time in a heated drying room, the paper shell - keel and gunwales attached - was removed from the mold for finishing. The boat builders completed a proprietary waterproofing process, added sealed air chambers for flotation, installed a paper deck, and fitted the hull with the proper hardware, ribs, and other woodwork. When finished, one observer noted, the racing shells were like polished steel, 12 inches wide and finished as beautifully as a piano body

.

For a rowboat or canoe, the basic hull manufacturing technique was nearly identical, except that only one sheet of thick linen paper from the Crane Mill in Dalton, Massachusetts, was used, still damp and in roll form. When dried, the hull still measured no more than 1/8 to 1/10 inch thick.

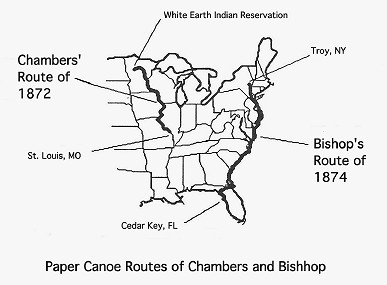

As mentioned, the paper rowing shells acquired early acceptance by major professional and collegiate rowers. Equal fame was brought to Waters products by two canoe adventurers of the day. A young reporter for the New York Herald, Julius J. Chambers, ordered a Waters canoe, to explore the Mississippi headwaters and then to continue downstream to New Orleans. The canoe reached him by rail at St. Paul in May 1872, enabling him to set off from the White Earth Indian Reservation in central Minnesota. By June 9 he had arrived at Lake Itasca and explored its tributaries to the great interest of his paper's readers. He continued downstream but grew weary of the summer heat and aborted his trip just short of St. Louis, continuing on to New Orleans by steamboat.

As mentioned, the paper rowing shells acquired early acceptance by major professional and collegiate rowers. Equal fame was brought to Waters products by two canoe adventurers of the day. A young reporter for the New York Herald, Julius J. Chambers, ordered a Waters canoe, to explore the Mississippi headwaters and then to continue downstream to New Orleans. The canoe reached him by rail at St. Paul in May 1872, enabling him to set off from the White Earth Indian Reservation in central Minnesota. By June 9 he had arrived at Lake Itasca and explored its tributaries to the great interest of his paper's readers. He continued downstream but grew weary of the summer heat and aborted his trip just short of St. Louis, continuing on to New Orleans by steamboat.

Two years later, Nathaniel Holmes Bishop and an "assistant" (a New Jersey waterman hired for the trip) pressed south from Quebec in an 18-foot, 300-lb. decked wooden "canoe", propelled alternatively by two sets of oars and a single sail. Arriving in Troy, Bishop learned about Waters' paper canoes, whereupon a feeling of buoyancy and independence came over me . . . with the consciousness that I now possessed the right boat for the enterprise.

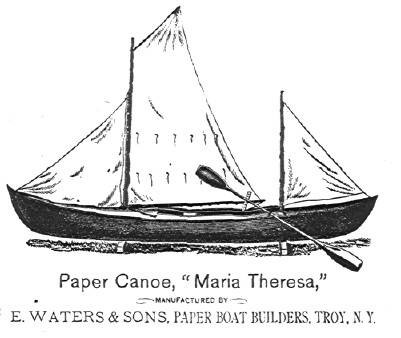

He had his assistant return to NJ, procured a paper canoe, and after a short hiatus continued alone aboard his new canoe the "Maria Therese" eventually arriving at Cedar Key on the Gulf Coast of Florida. He chronicled his trip in a book "The Voyage of the Paper Canoe" which sold well both in the United States and Europe. While the illustration shows a double bladed paddle, most of the journey was actually accomplished using oars. This lead to a rather petulant review of Bishops book in the New York Times, claiming that it really was not true "canoeing" as paddles were not involved in the propulsion.

While the Waters were initially (and exclusively) known for boat manufacture, their minds apparently remained at work on other projects and other opportunities. In 1878, they built a paper observatory dome for the newly erected Proudfit Observatory at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy. The construction method was almost identical to that used for paper canoes; thick linen paper was formed over a mold of a dome segment that already contained a wooden framework which was removed from the mold with the paper. Finished sections were bolted together and the joints were weatherproofed with cotton cloth saturated with white lead.

While the Waters were initially (and exclusively) known for boat manufacture, their minds apparently remained at work on other projects and other opportunities. In 1878, they built a paper observatory dome for the newly erected Proudfit Observatory at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy. The construction method was almost identical to that used for paper canoes; thick linen paper was formed over a mold of a dome segment that already contained a wooden framework which was removed from the mold with the paper. Finished sections were bolted together and the joints were weatherproofed with cotton cloth saturated with white lead.

Waters built a several domes thereafter. In 1881 the largest of their domes was placed on a new observatory at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. It was 30 feet 8 inches in diameter and contained over 2,000 pounds of paper. In 1883 Beloit College, in Beloit, Wisconsin, erected an observatory using a Waters' dome, this time of smaller dimension, and in 1885 a new high school in Taunton, MA was graced with a Waters dome. Other domes credited to Waters were at Columbia College in New York City and Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. George Waters obituary in a Troy newspaper would have us believe that there were several other domes, but their locations remain unknown. For more information on Domes, see the page accessed from the home page.

Waters & Sons apparently remained an active business through the end of the century. In addition to their traditional products they experimented with a steam launch hull built for Westinghouse (to try with one of their steam engines) as well as a whaleboat for evaluation by the US Navy, but clearly the business was winding down as they relocated to smaller quarters in 1898.

The end came suddenly in 1901, when George Waters accidentally started a fire while applying finishing touches with a blowtorch to a shell destined for Syracuse University. The factory and all its contents were declared a total loss. We can thus credit George with both the birth and death of the paper boat era. George and his father, Elisha, died shortly thereafter, (in 1902 and 1904 respectively).

(For more on Rowing shells try another page on this site.)

Return to The Main Page for more information on 19th Century Paper technology!